Oriel Myrddin Gallery, Carmarthen 2010

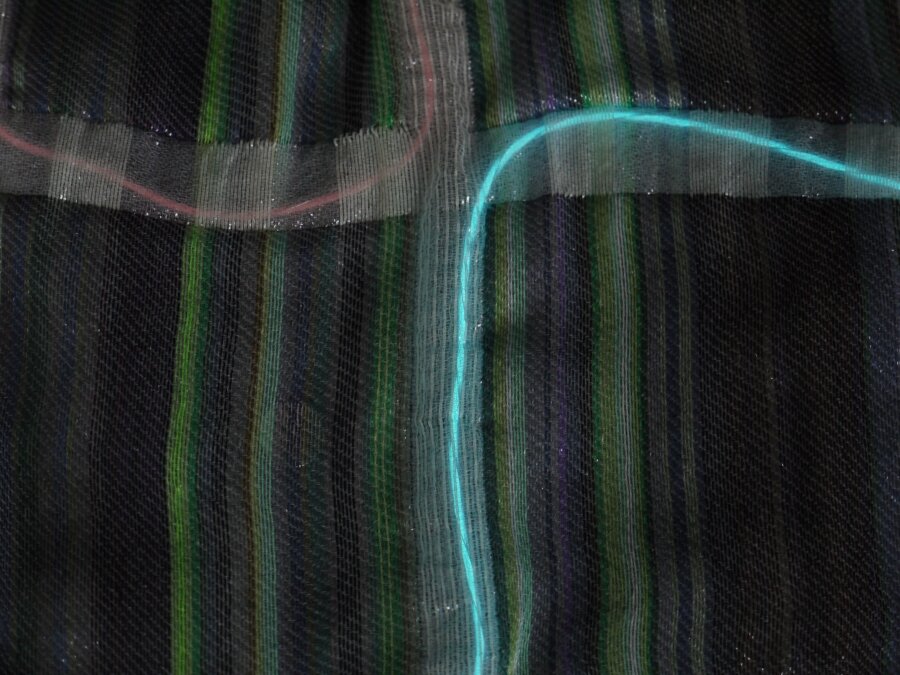

Warp + weft catalogue. Image on front cover is by Ptolemy Mann.

Warp + Weft: catalogue introduction

Weavers are a rare breed. Invariably the least popular pathway on textile degree courses, weaving is seen to be too slow, too technical, too prescriptive, too flat, too restrictive and with no margin for error. It’s certainly not an option for those who want quick results and instant gratification. The choice to weave is an unforgiving path to follow.

But it is these very challenges that weavers relish. To be a weaver requires great discipline, patience and a commitment to ‘hard work’, but the rewards are palpable. Many years of study are required to build the requisite vocabulary – the weavers’ ‘craft technology’ skills are the foundation upon which design and artistry are built. You also need to embrace the prescribed boundaries that the loom commands – the vertical warp and the horizontal weft – and then with an intellectual dexterity strive to challenge those very boundaries; to work with them and against them at the same time.

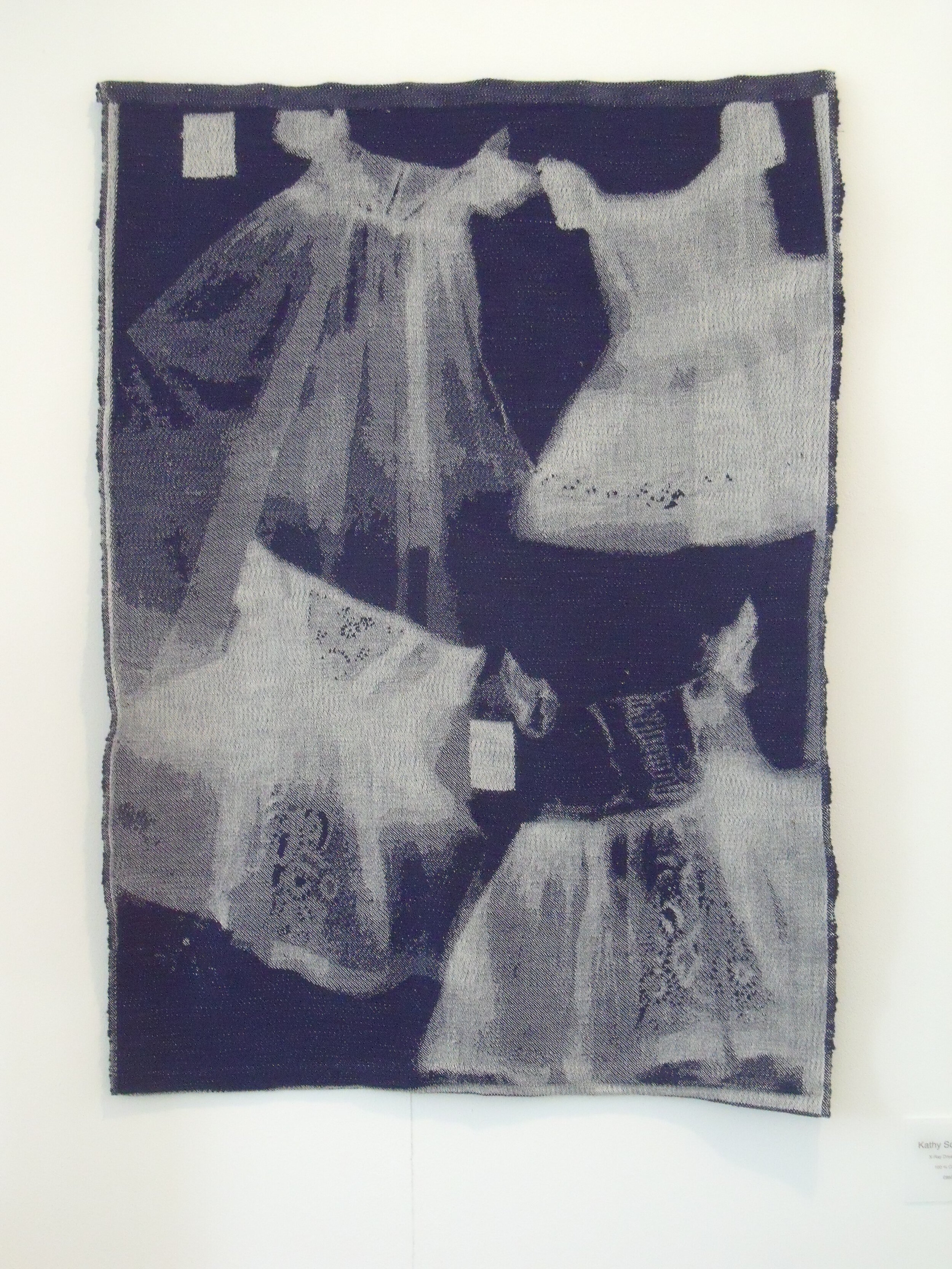

The connecting thread for the work selected for this exhibition, is that all the artists take a decidedly unexpected approach to weaving. There is a reverence for tradition deftly interwoven with an enthusiasm for new technology, new aesthetics and new making methods. To the initiated, the exhibits do not show what you’d expect to find in a weave show. My aim is for preconceptions about this most ancient of crafts to evaporate.

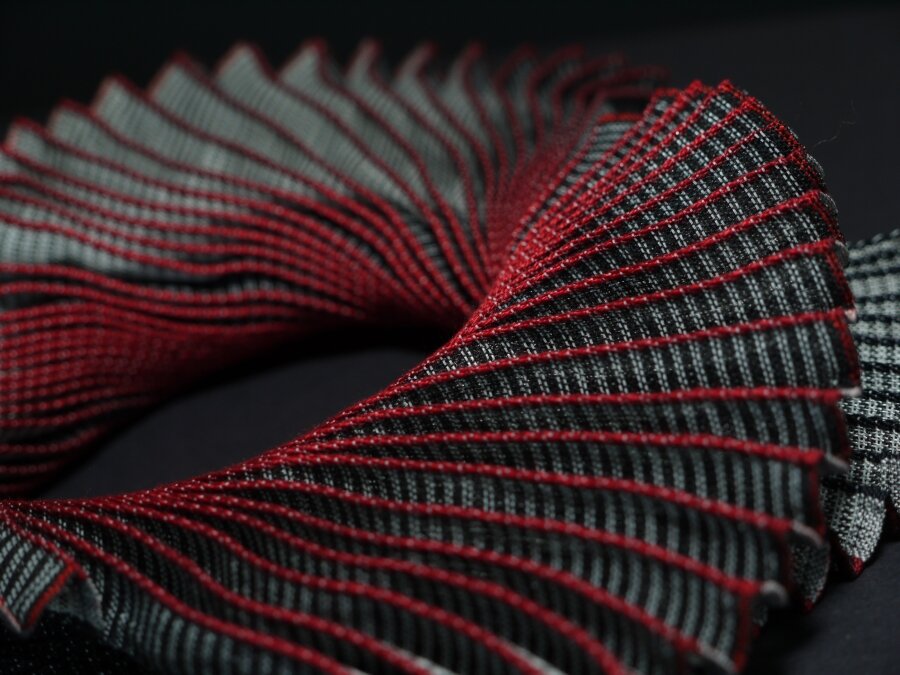

The works all share an aesthetic elegance underpinned with true technical ingenuity. Ann Richards’ delightful pleated necklaces are self forming; a careful combination of structure, yarn and finish result in a delicate yet decisive work that invites curiosity. Ismini Samanidou’s collaborative work with Gary Allson is a work in progress; a conversation in materials and techniques stemming from her time spent with a traditional reed maker in Bangladesh. ‘To weave’ has itself become the concept behind her intriguing series of sketches, interpreted and investigated through mechanical drawing, CNC routed wooden planes, hand woven cloth and power loomed jacquard.

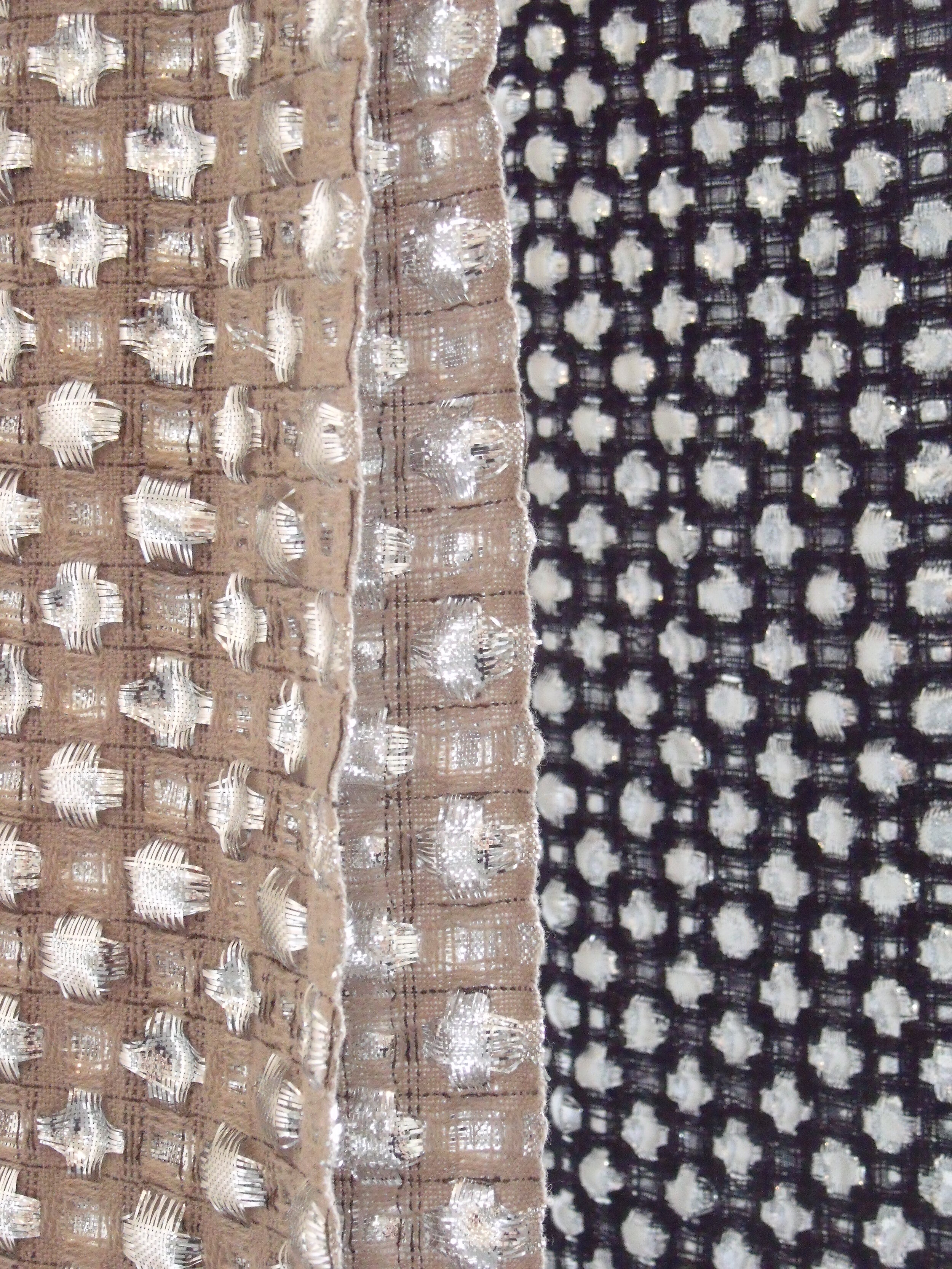

The unfussy and disciplined nature of the weaver is self-evident in the palette of most of the exhibits – refinement and precision of colour is common – an almost minimalist approach to allow the structure, surface, and texture to breathe on an equal footing with the visual impact of colour. Where colour is embraced, most notably by Ptolemy Mann, the sophistication of the joyful palette is hypnotic. Elsewhere in Makeba Lewis’ neckpieces the colour blocks act as eloquent punctuation in an otherwise sparse palette of black, white and metal yarns where the vocabulary of the surface and fabric handle dominates.

All weavers are obsessed with structure and thus the method of making is a critical element of the visual language. Every minutiae of the construction needs careful consideration: the fibre, the yarn, the colour, the structure, the density, the finish, the make-up. All of the exhibits exemplify this approach, but particular reverence must be given to Peter Collingwood and Ann Sutton, two great weavers, that any weave student cannot fail to have been inspired by.

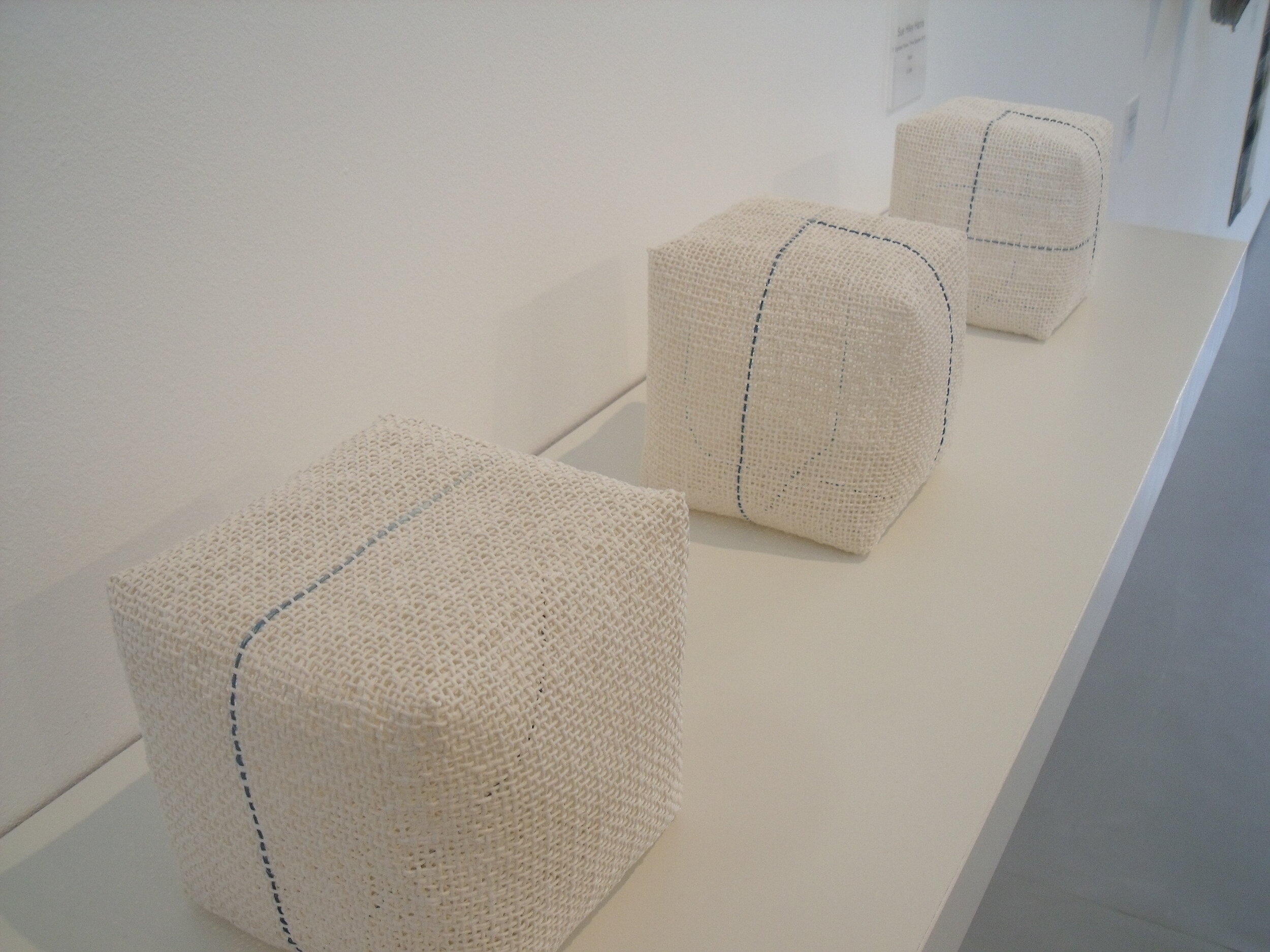

Ann Sutton’s status in the world of weaving is unparalleled. Her long career in textiles has unselfconsciously spanned everything from commercial furnishing design to pure ‘art’ textiles. The tensions and hierarchies between the art, craft and design spheres have been ignored in favour of embracing a celebratory constructivist exploration of weaving. Whilst she is well known for her saturated colour spectrum works, for this exhibition I focused on another recurring theme in her work over decades; the perfection of the most fundamental weave structure, plain weave and the geometric perfection of the square. This preoccupation is highlighted by sculptural works from 1968 and a framed textile from 2009.

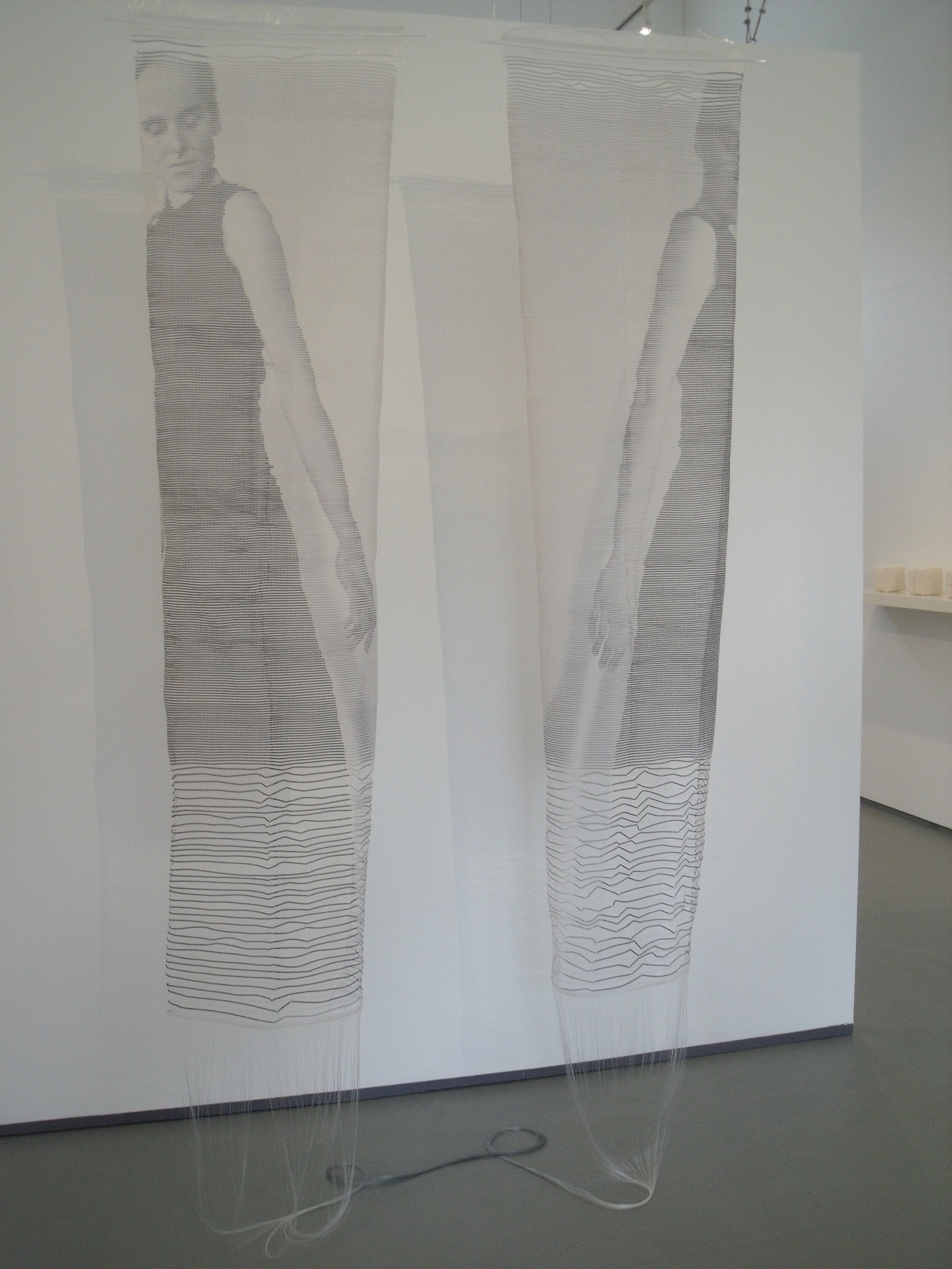

Peter Collingwood, with his formal background in medicine, approached weaving in an uninhibited fashion and as a result of his ‘what if’ approach developed a completely new way of weaving which he christened ‘Macrogauze’. Delightfully un-precious, he literally chopped up his looms’ shafts and reeds to allow him to weave in a way that meant warp threads no longer had to stay in a fixed position during the weaving of a length. His majestic wall hangings exploring this technique became his trademark. He exploited the beauty of the unwoven warp by crossing the threads over each other in a rigorous palette of black and undyed linen. It was with enormous sadness that Peter passed away in the early days of planning this exhibition before an invitation letter to participate was sent. It is therefore with huge gratitude that I thank the Crafts Study Centre for their generous loan of the Macrogauze hanging featured in this exhibition at Oriel Myrddin.

I also wish to thank Meg Anthony, the curator of the Oriel Myrddin, for this wonderful opportunity and the trust she placed in me to compile this show. I also thank her for her considered selection of our catalogue designer Heidi Baker and photographer Toril Brancher for their equally intelligent and thoughtful approach to the project.

It has been a real personal treat to curate this show and I hope you share in my delight in this selected exhibits. I hope too that it’s not what you expected...

Laura Thomas, 2010